Understanding how Peru’s landscapes might change in the future requires more than running computer models. It calls for a process that brings together people with different experiences, values, and areas of expertise. In NASCENT-Peru, we combined stakeholder participation, scientific evidence, and scenario modelling to explore nature-positive futures and their potential implications. The scrollytelling below takes you through this process step by step, from the first ideas shared in workshops to the final scenarios used in our simulations. Scroll down to explore the process.

The NASCENT-Peru project focuses on creating and modelling normative, nature-positive scenarios for future landscape development in Peru. These scenarios are then assessed for their ecological and economic impacts, and the findings are communicated to relevant stakeholders.

The first step is the creation of the normative, nature-positive scenarios. But, before we discuss the scenario creation we want to clarify what is ment with “normative scenarios”.

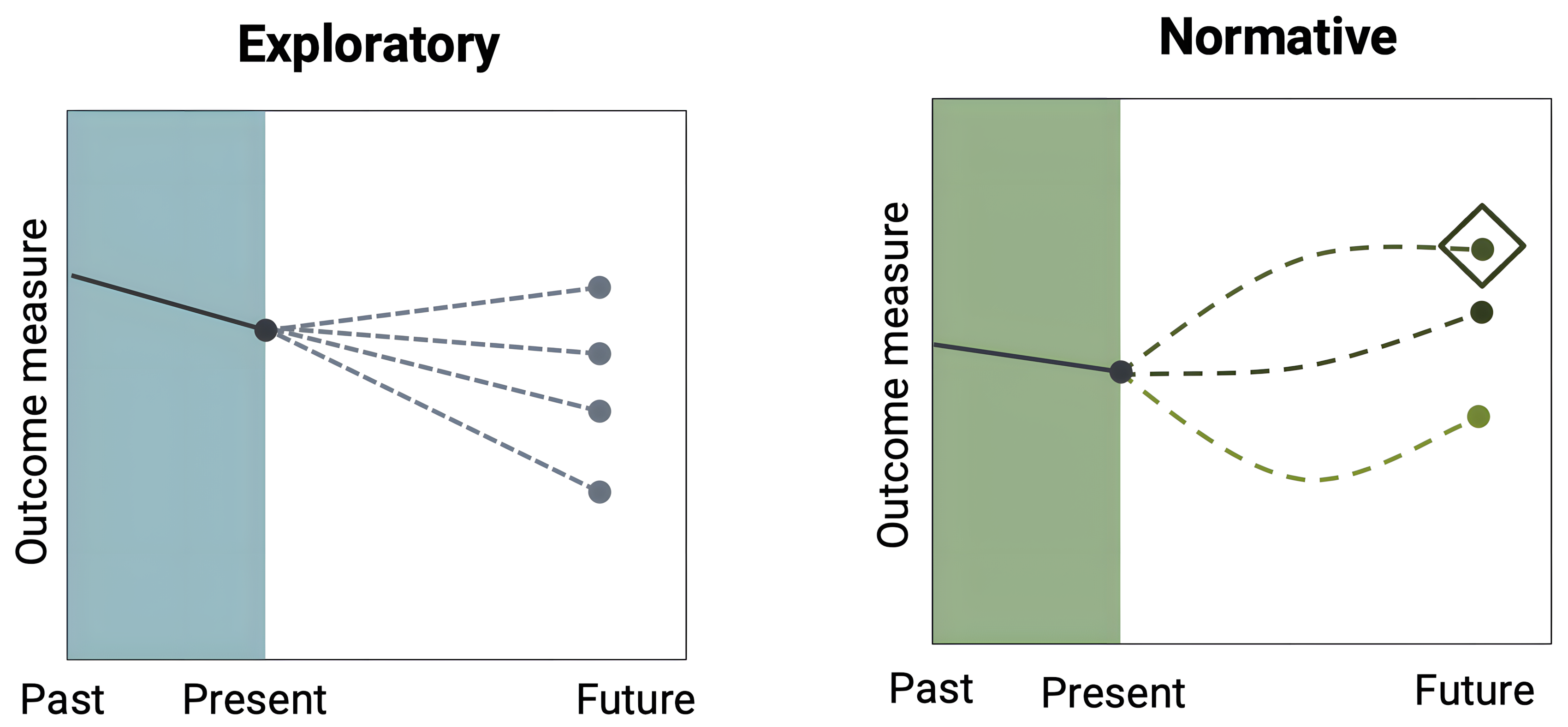

The best way to understand normative scenario analysis is to contrast it with the the type of scenario analysis we commonly see which is exploratory scenario analysis. Both types begin by analysing the historical trend for a given measure of interest and then use that trend to predict how the measure will change from the present into the future.

Exploratory scenario analysis illustrates the range of possible future outcomes. It typically centres on a business-as-usual scenario extrapolated from current trends. Alternative futures are then defined as small deviations from that baseline. Such scenarios are often devised in a ‘top-down’ manner by experts. As a result, they offer no insight into the societal desirability of their outcomes.

By contrast, normative scenarios are centred around specific desirable future endpoints. Rather than predicting the single most likely future, they open up space for deep, transformative change. They are typically devised with stakeholder participation, which allows them to incorporate diverse value perspectives. This participation can engage and mobilise actors and encourage stewardship in realising the scenarios’ goals. Therefore, we aimed to create normative scenarios in NASCENT-Peru.

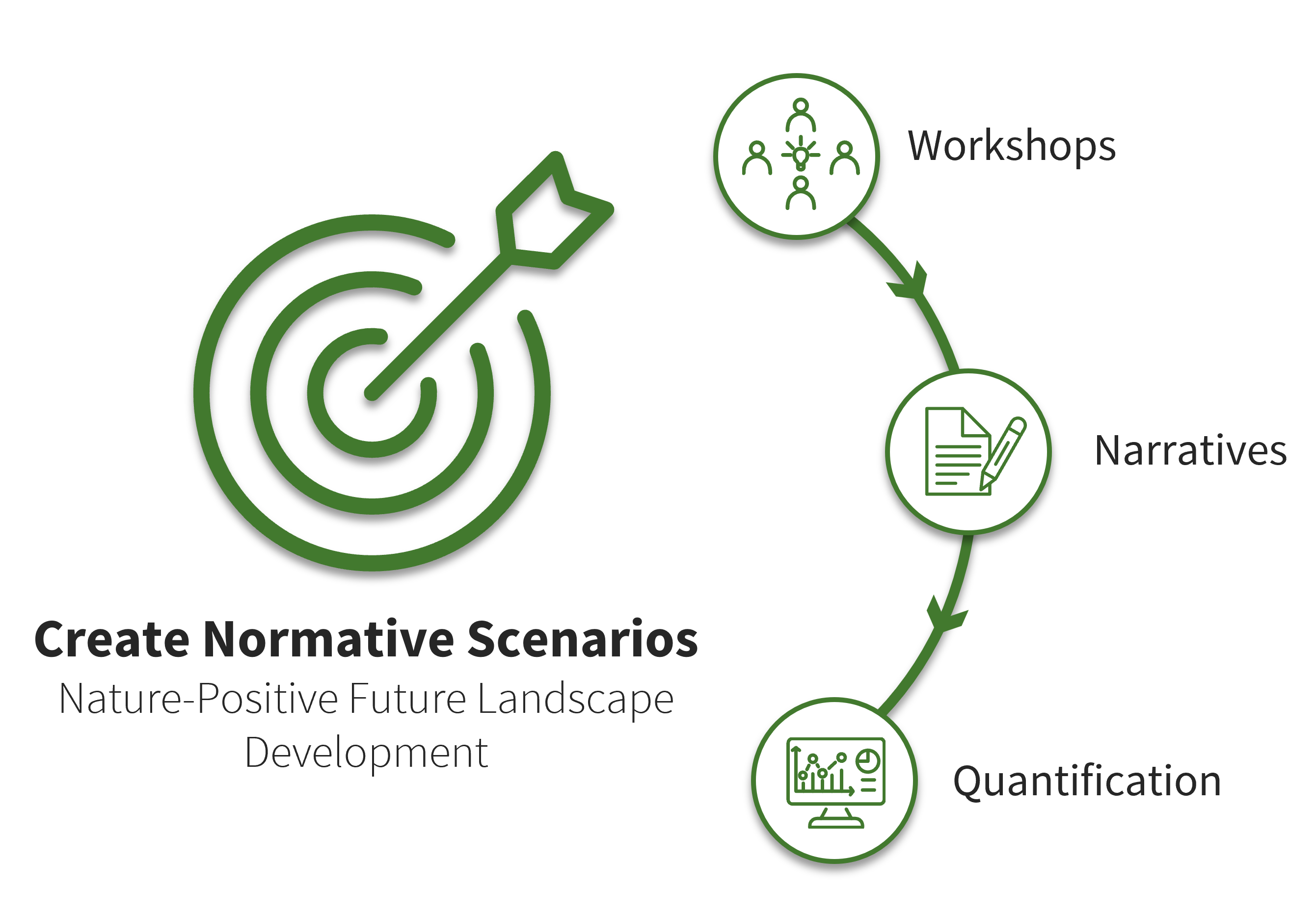

In our project the workflow for creating normative nature-positive scenarios comprises three main steps:

1. Conducting workshops with relevant stakeholders to discuss future landscape development in Peru.

2. Drafting future-development narratives based on the workshop outcomes.

3. Quantifying narrative content using scientific literature to generate inputs for our computer models.

So let’s start with the workshops.

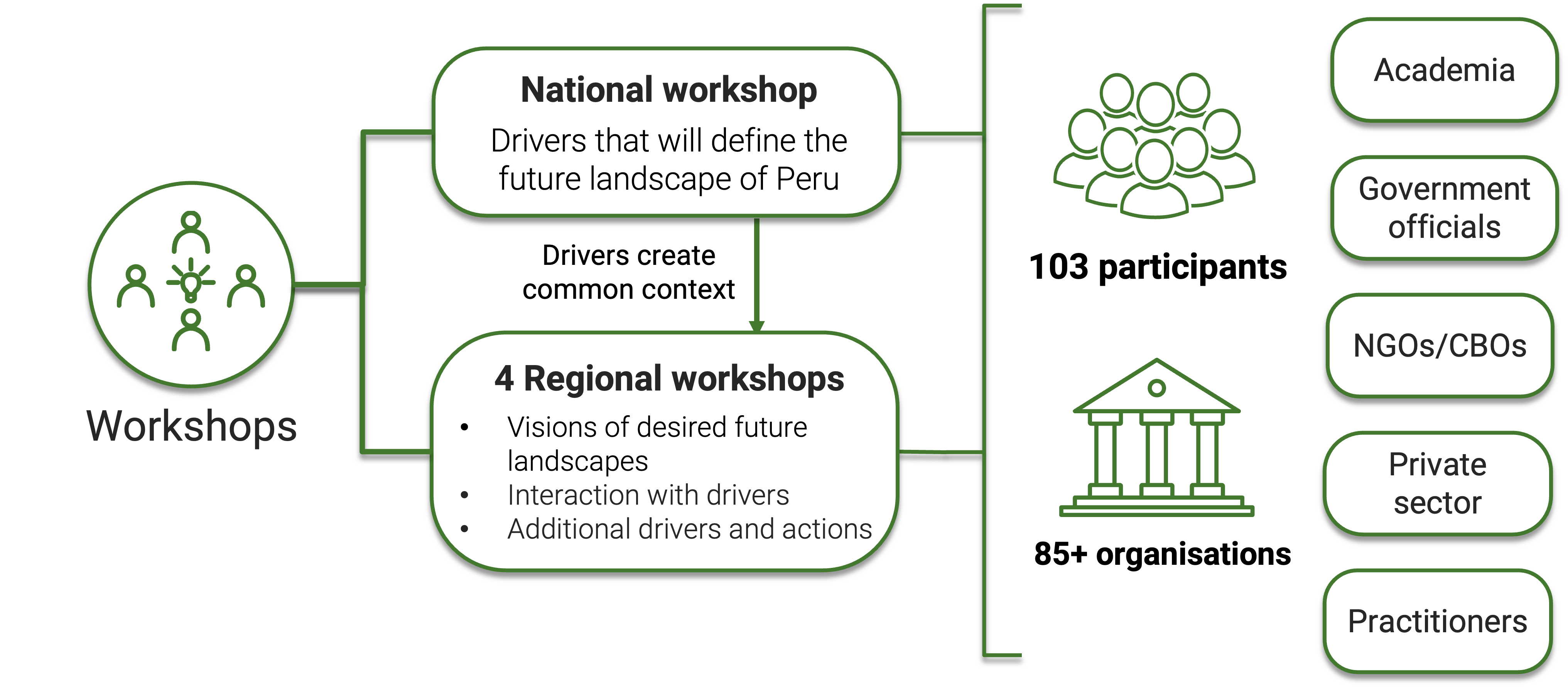

In May and June of 2024 we conducted a series of 5 workshops in different regions across Peru. We started off with a national workshop in Lima followed by four regional workshops in Piura, Puerto Maldonado, Huaraz and Tarapoto.

At the national workshop in Lima, participants took part in a series of exercises involving individual tasks, group discussions, and plenary sessions to:

1. Identify the key drivers shaping Peru’s future landscape.

2. Group those drivers into Social, Technological, Ecological, Economic, and Political categories.

3. Rank each driver by its anticipated impact on the landscape.

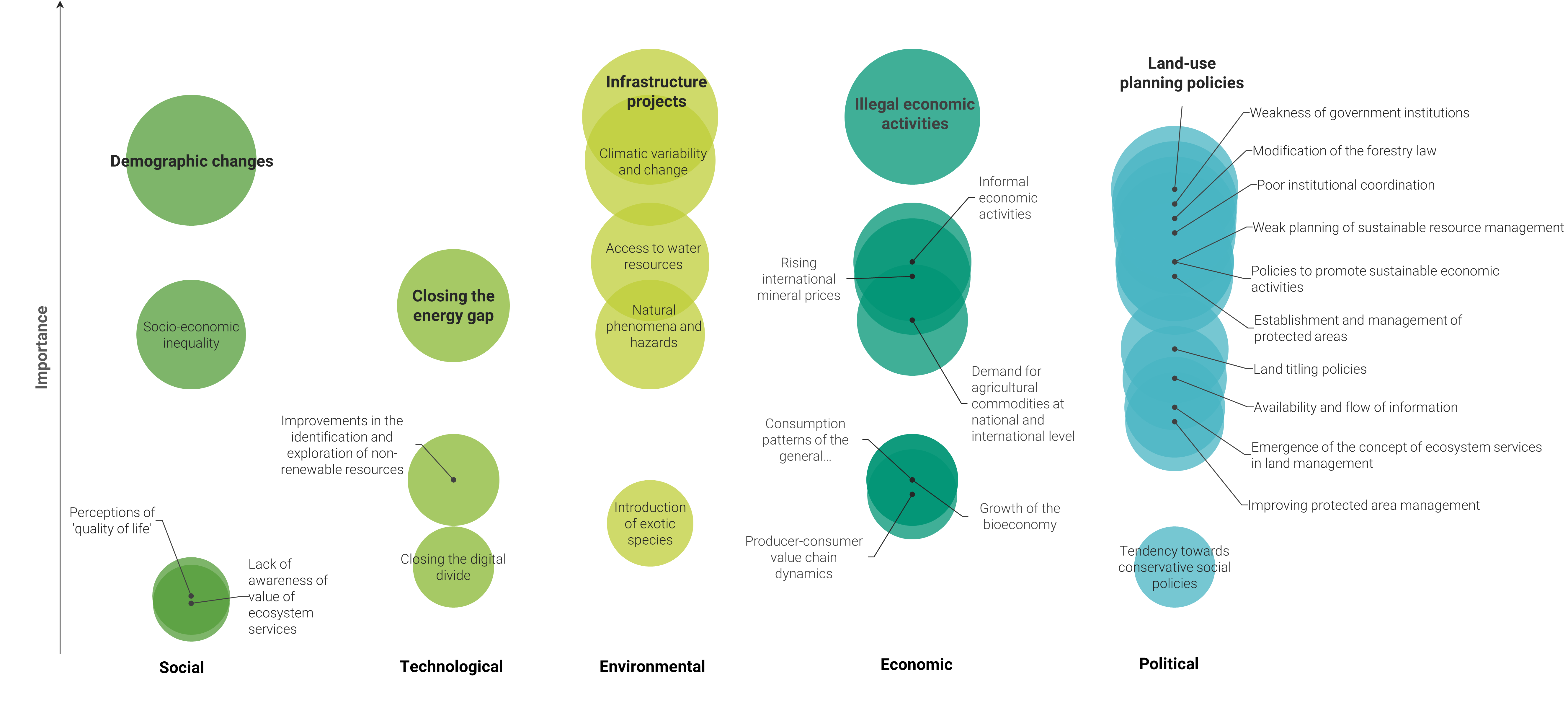

The results of this ranking are shown in the bubble chart. The Political category leads in term of the number of drivers considered important (higher on the vertical axis). Its principal drivers are land-use planning policies (zoning and land ownership), weakness of government institutions (insufficient administrative capacity and widespread public distrust), modifications to forestry law (concession rules and enforcement mechanisms) and poor institutional coordination (overlapping mandates and unclear responsibilities). For the other categories, the single most significant drivers are:

• Social: demographic change (population growth and urbanisation)

• Technological: closing the energy gap (grid extension and reliable supply)

• Environmental: infrastructure projects (roads and dams)

• Economic: illegal economic activities (informal mining and logging)

Following the national workshop, we held four regional workshops and applied the Three Horizons Framework to guide discussions about the landscape across different temporal states.

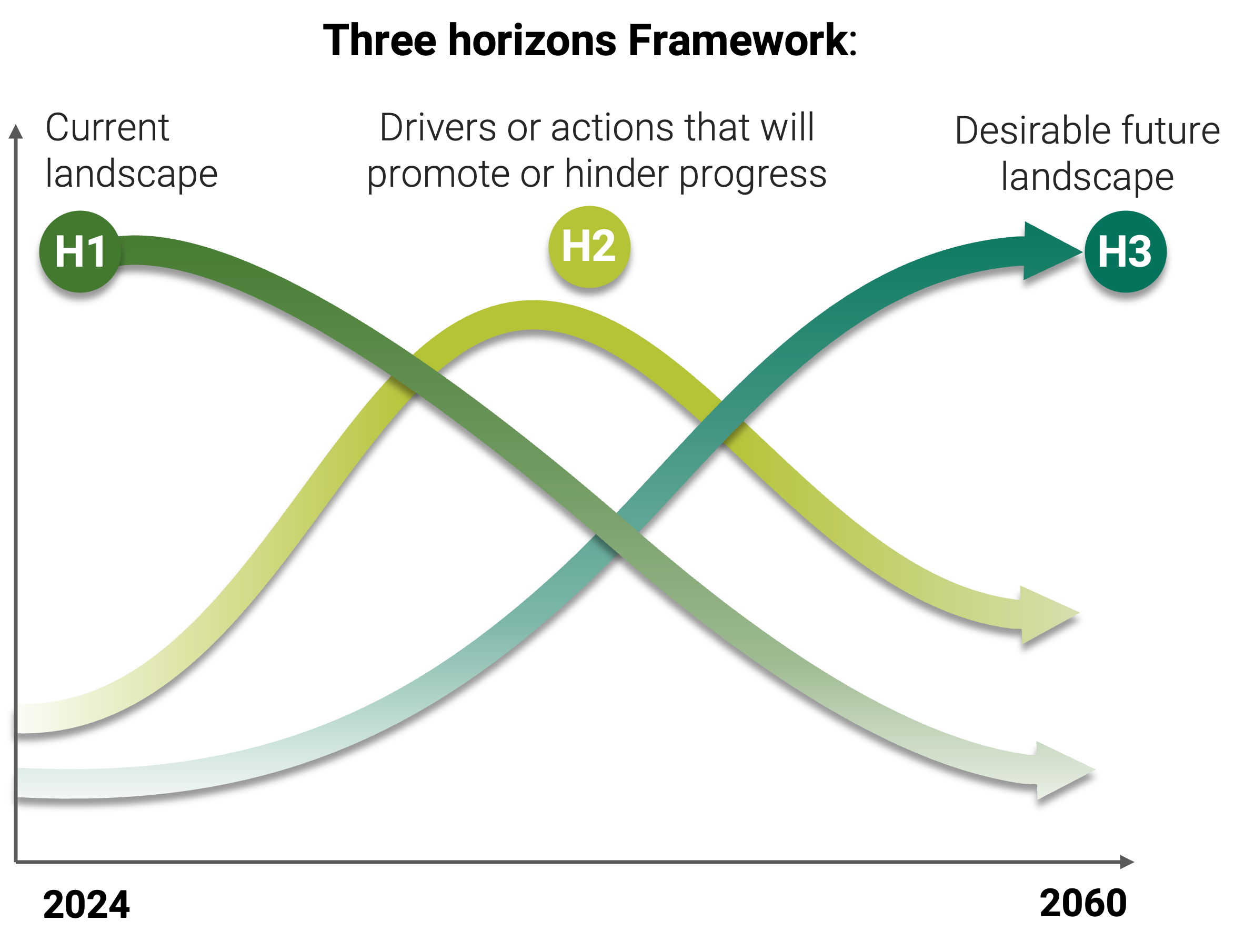

The Three Horizons Framework divides system change into three time-based horizons:

• Horizon 1: the established, current state of the system

• Horizon 2: the emerging drivers or actions that reinforce or challenge that state

• Horizon 3: the aspirational, long-term future state

We adapted this framework for our workshops by defining Horizon 1 as each region’s current landscape, Horizon 2 as the national drivers identified in Lima that could support or impede change to the landscape, and Horizon 3 as the desirable future landscape envisioned by participants.

In each of the regional workshops, participants worked through a series of interactive exercises to:

1. Characterise the current landscape in their region (Horizon 1).

2. Define a desirable future landscape (Horizon 3).

3. Evaluate the national drivers, judging for each whether it would support or impede the transition from the current landscape to the desirable future landscape (Horizon 2).

In total, the five workshops brought together 103 participants from more than 85 organisations. They represented five stakeholder groups:

• Academia

• Government officials

• NGOs/CBOs

• Private sector

• Practitioners

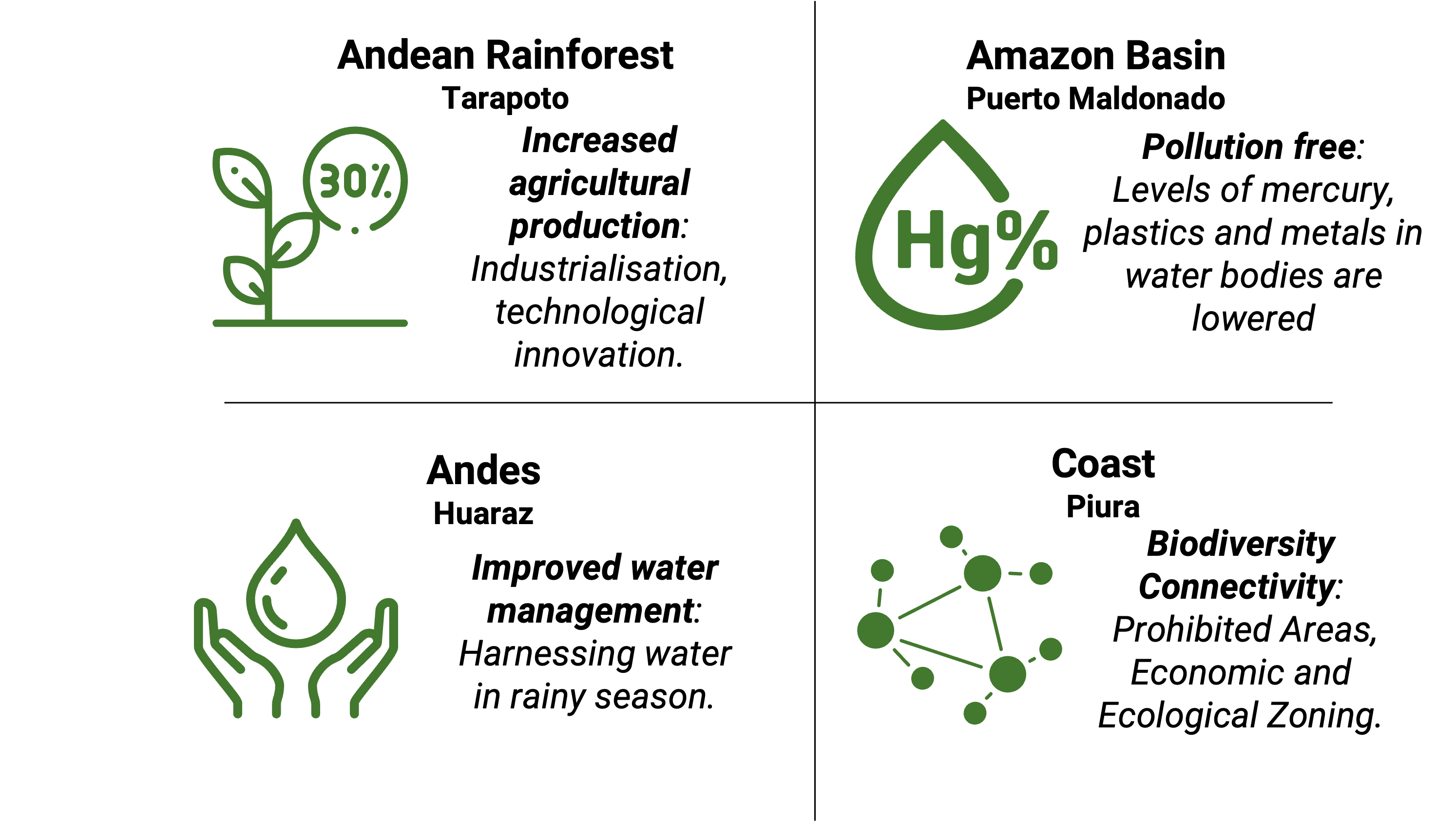

Together, the stakeholders identified over 700 statements describing desirable future landscapes in Peru. In each regional workshop, certain priorities emerged from the discussions about these envisioned futures. In the Andean Rainforest (Tarapoto), this was agricultural production through industrialisation and technological innovation. In the Amazon Basin (Puerto Maldonado), it was reducing mercury, plastics, and other contaminants in rivers and soils. In the Andes (Huaraz), it was improved water management by capturing rainy season flows for year-round supply. On the Coast (Piura), it was biodiversity connectivity through expanded protected areas and the alignment of economic planning with ecological zoning.

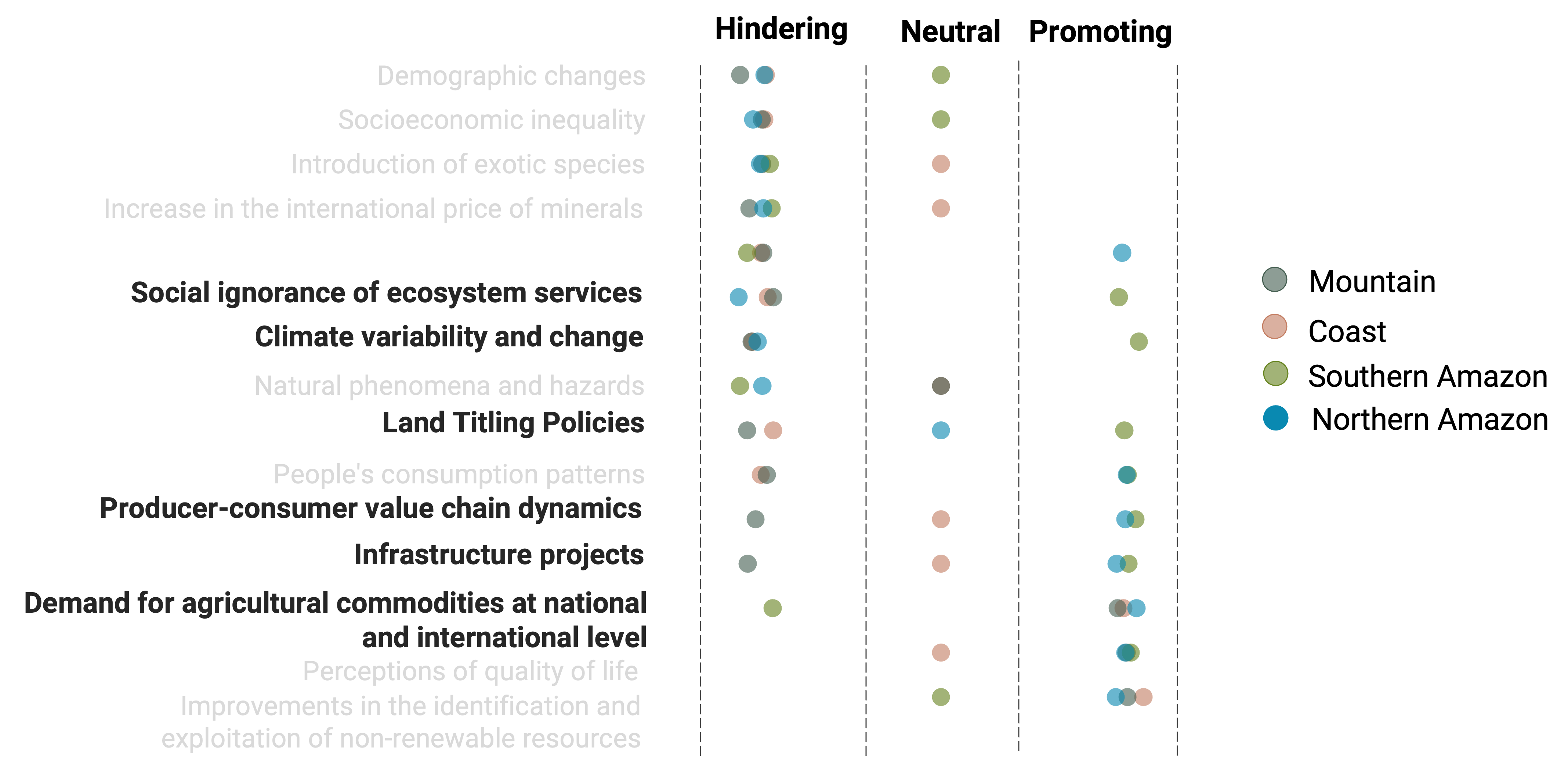

The regional workshops also revealed differing perspectives on whether certain drivers would support or hinder progress towards the desired future landscapes. The drivers highlighted in bold in the graphic are those where the workshops expressed particularly divergent views regarding their influence on achieving regional visions.

The workshop phase closed with a broad collection of ideas on Peru’s future landscapes, highlighting regional priorities and areas of disagreement on key drivers.

Building on this foundation, the next step was to synthesise the information from all workshops into coherent narratives.

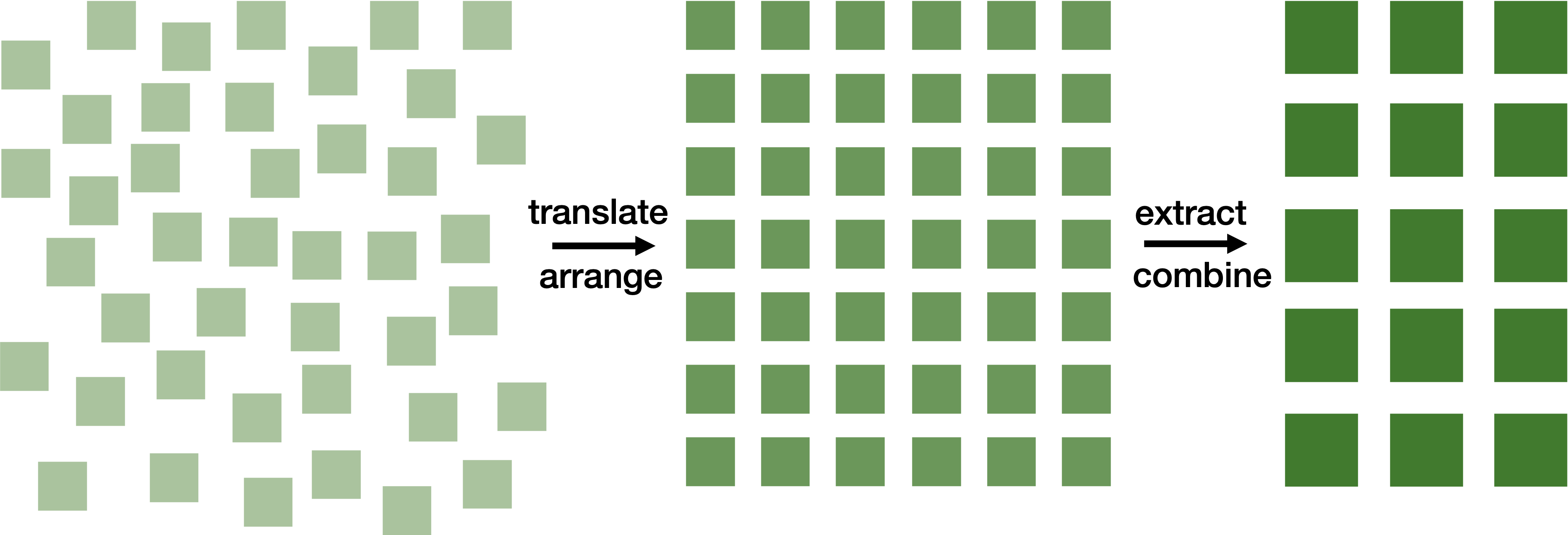

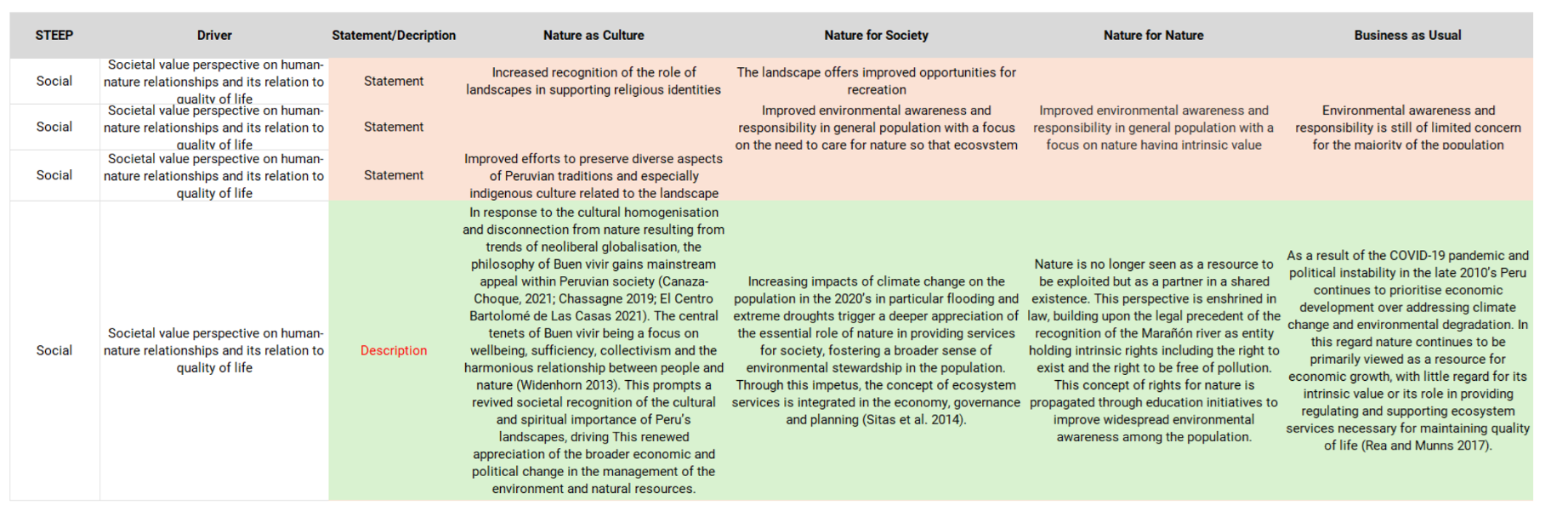

We translated all statements collected from the workshops into English, then extracted those describing desirable landscape characteristics. These statements were arranged systematically and combined where appropriate, resulting in a final set of 60 unique statements.

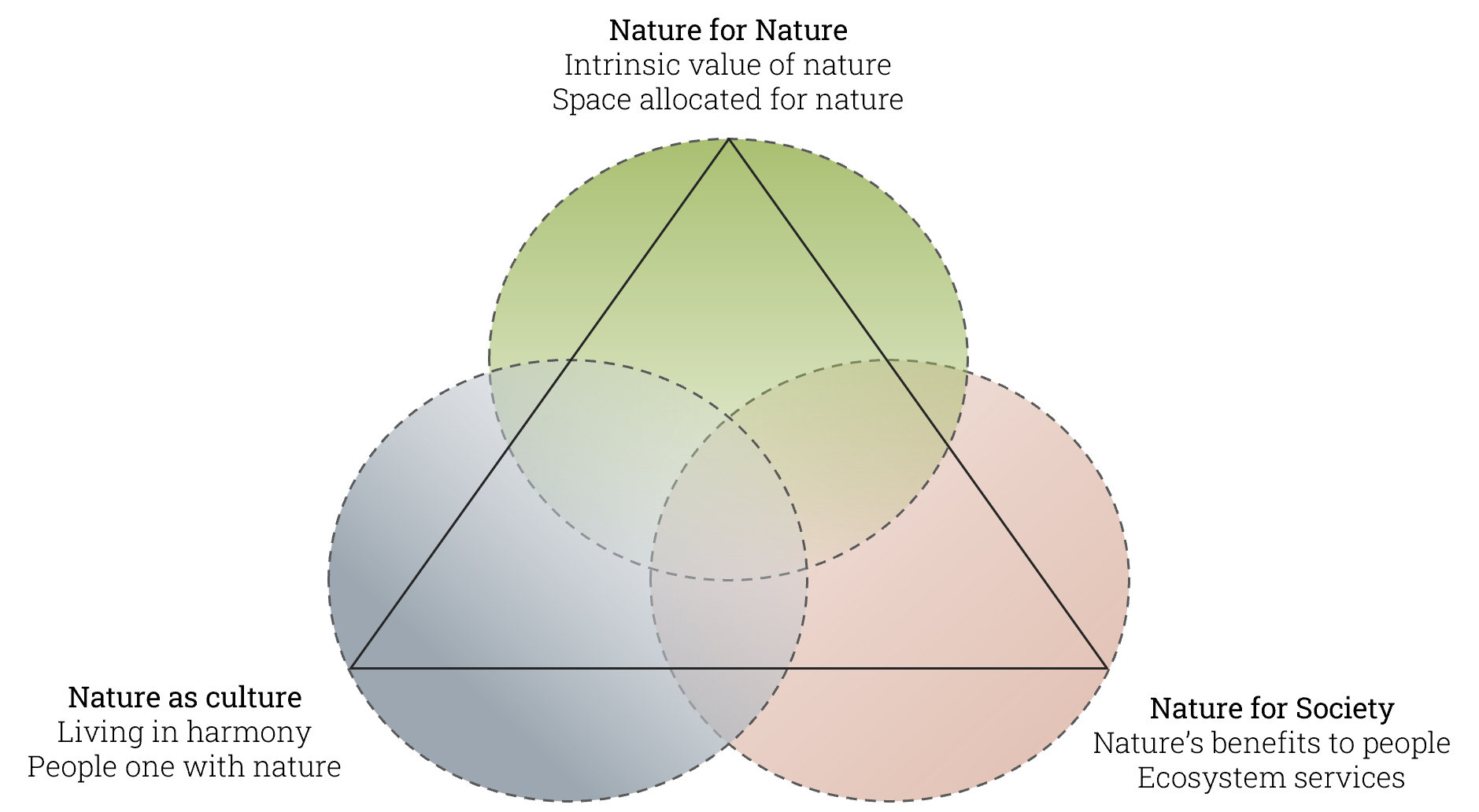

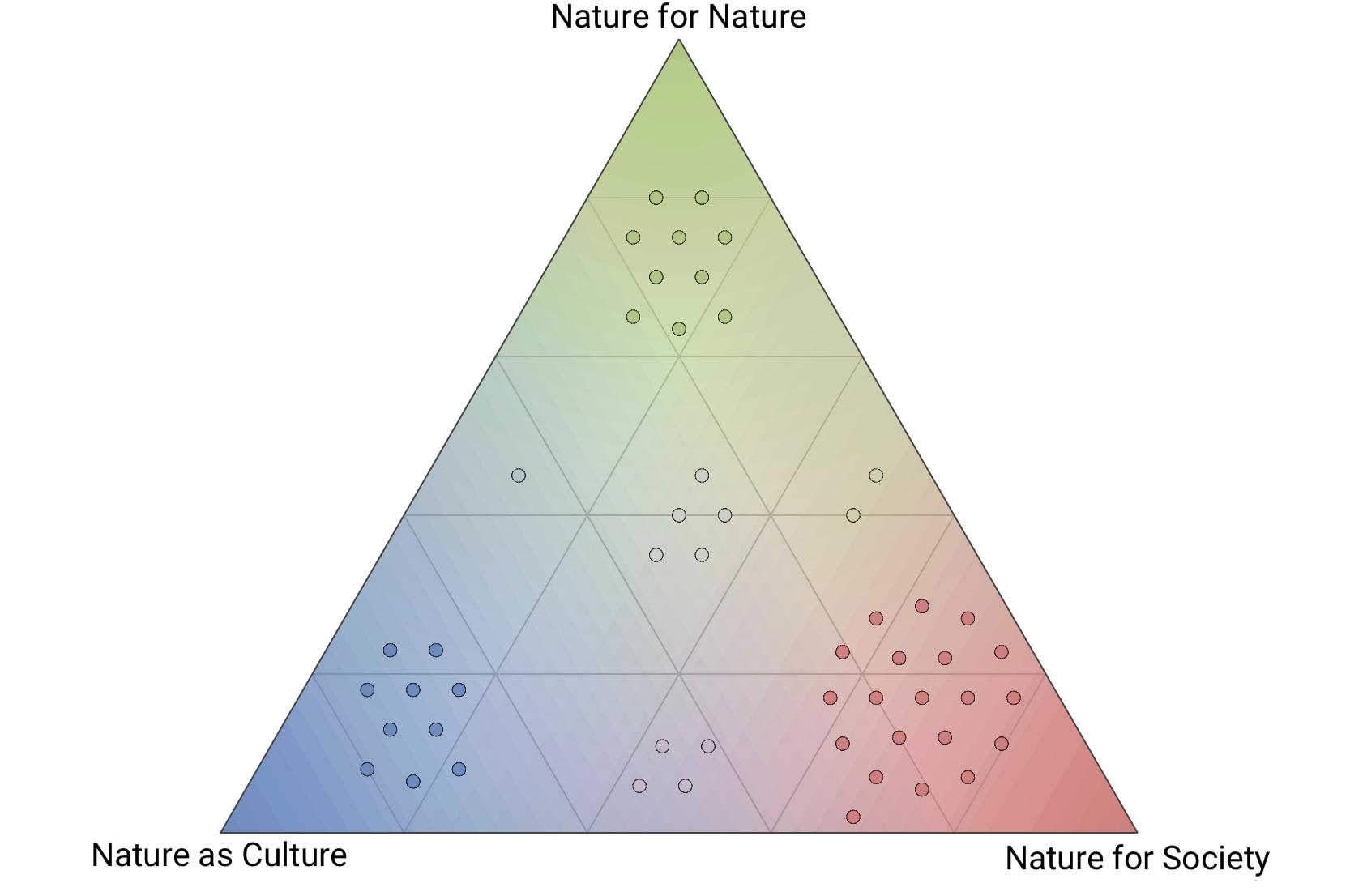

To prepare for narrative development, we organised the 60 unique statements into thematic groups using the Nature Futures Framework (NFF), developed by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). The NFF maps positive visions of human–nature relationships along three value axes:

Nature for Nature: viewing nature as having intrinsic value and deserving respect regardless of human benefit.

Nature for Society: recognising the instrumental value of nature in providing ecosystem services that support people.

Nature as Culture: valuing the relational connections between people and nature through culture, identity, and traditional practices.

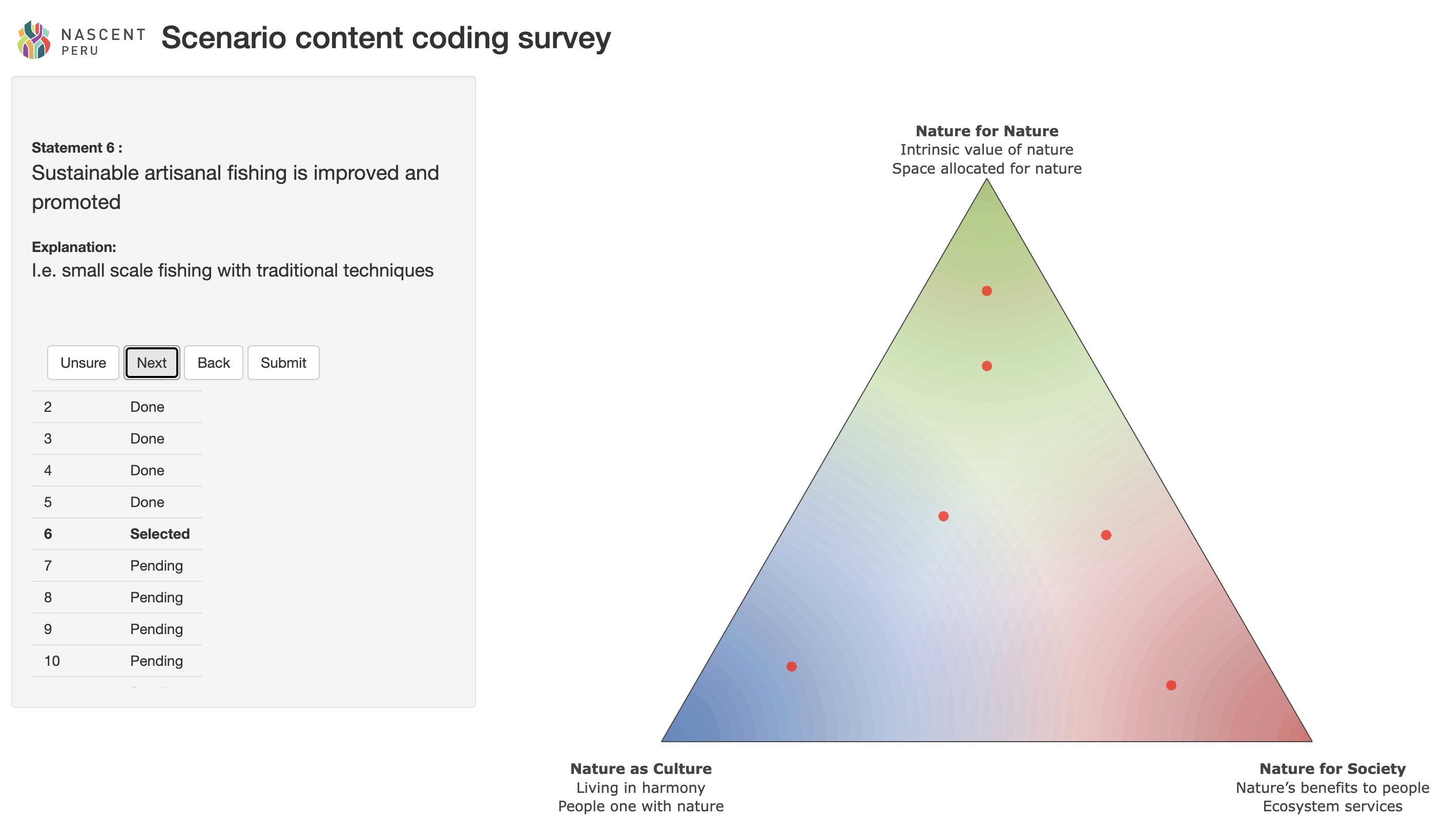

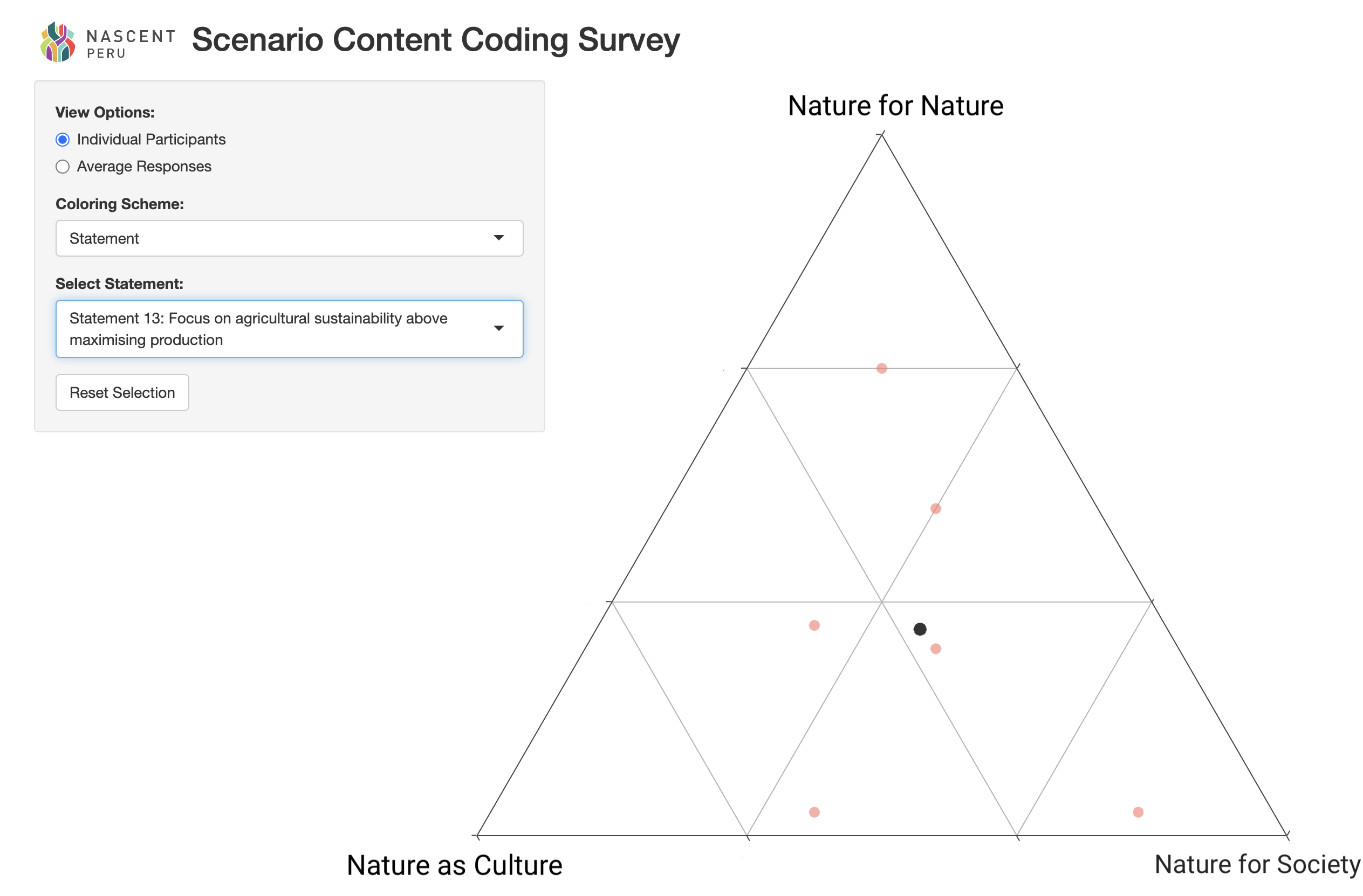

We then conducted an internal exercise in which each member of our research group individually positioned all 60 statements within the triangular space defined by the NFF, using a custom web application we developed for this purpose.

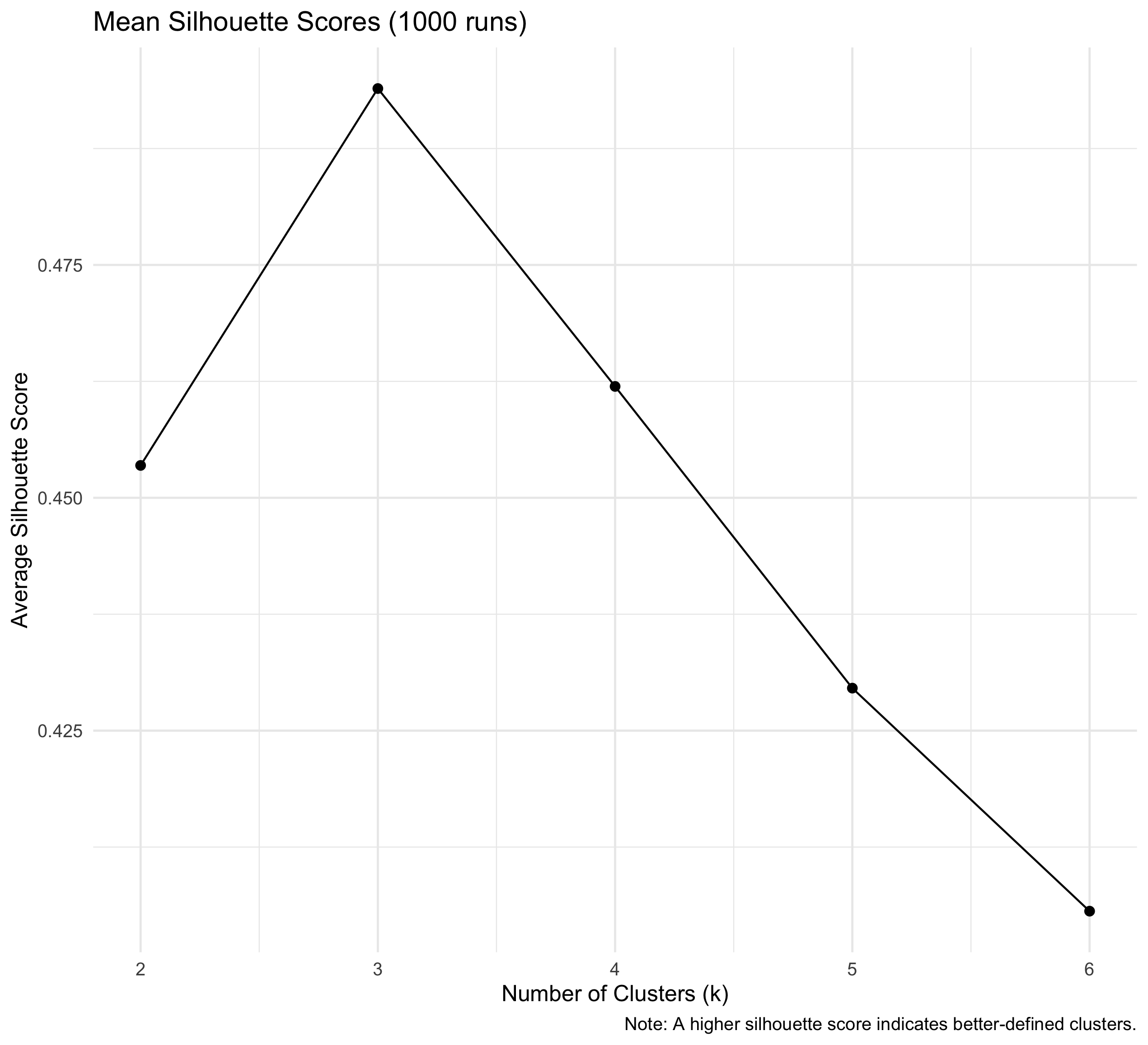

A subsequent k-means clustering was conducted to group the statements objectively. By calculating the silhouette score across 1000 runs per cluster number (k), we found that the optimal number of clusters was three. The resulting clusters each aligned closely with one of the three axes of the Nature Futures Framework.

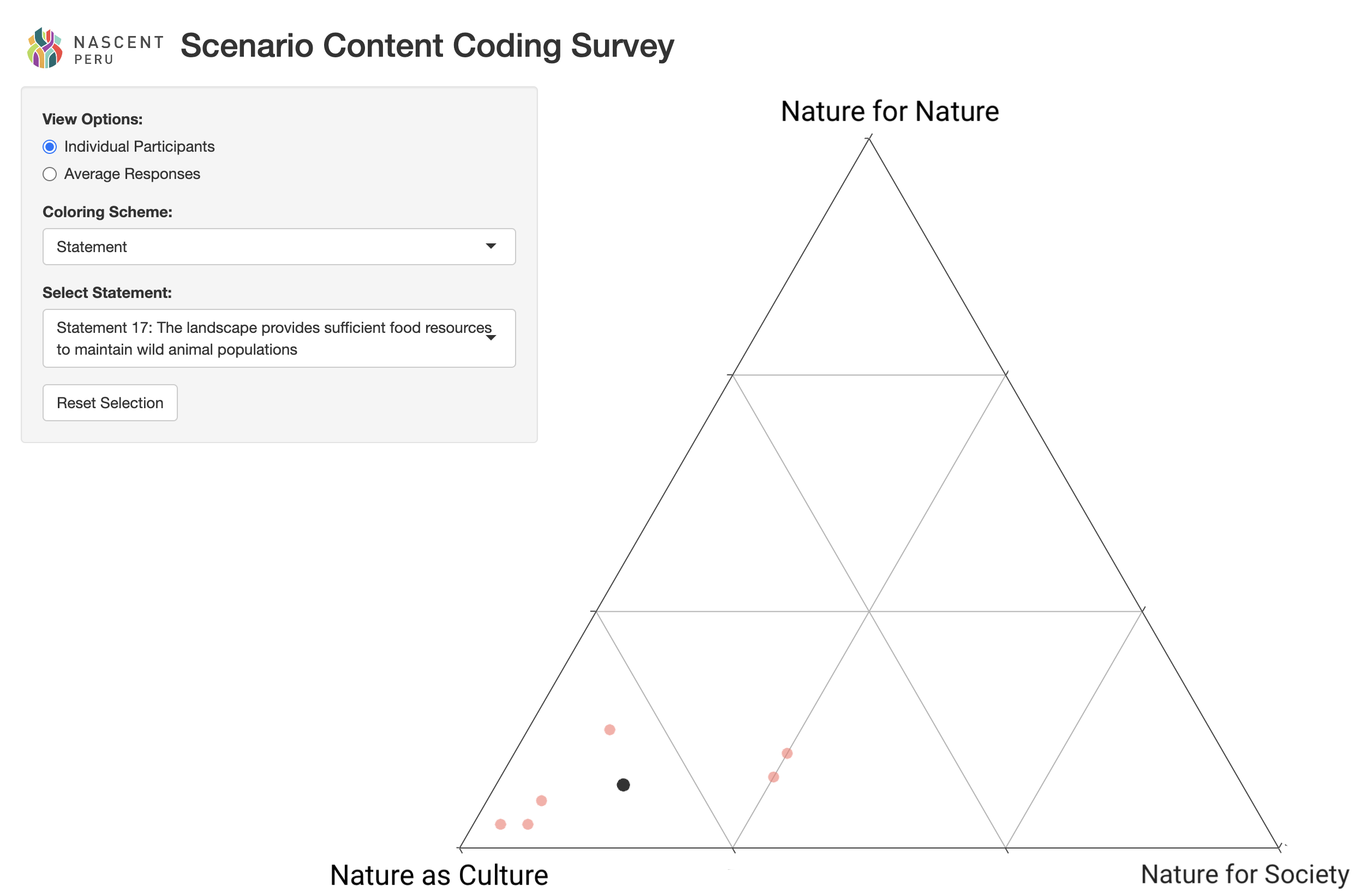

After assigning each statement to one of these three clusters, we assessed the level of agreement among individual placements. In the image, the red dots represent these individual responses, while the black dot indicates the average position.For some statements, there was strong agreement among individual responses regarding their placements.

There was more disagreement for others. In these instances, we discussed which of the three clusters best corresponded to the content of each statement and reached a consensus on the final placement.

In the end, each statement was assigned to one of the three axes of the Nature Futures Framework. Statements that corresponded to more than one value perspective are situated between the axes in the image. This grouping formed the foundation for developing the scenario narratives.

We summarised similar drivers from the national workshop into single, broader drivers where appropriate. In the next step, we linked each statement to the relevant drivers to describe how future landscape change could unfold in relation to each driver under each scenario. In addition to the three normative scenarios, each linked to one axis of the Nature Futures Framework, we also developed an exploratory Business as Usual scenario for contrast. All linked statements were further enriched with information from an extensive literature review.

Finally, we developed the narratives for each scenario through an iterative writing process, incorporating two rounds of feedback to ensure clarity and coherence. In each narrative, we systematically integrated the grouped statements, linked drivers, and insights from the literature review, grounding every scenario in both stakeholder perspectives and scientific evidence. As part of this enrichment, we also quantified certain aspects of the scenarios using literature sources, such as the projected number of inhabitants by 2060 or the share of the population living in urban areas.